How to Get a COI: USCG Certificate of Inspection

Introduction

So you want to run a commercial passenger ship in the USA? Maybe you plan to start a small ferry service. Or run a dinner cruise? Better yet, a whale watching tour. No so fast. Before you venture into this new business, we need to get a COI. Abandon hope all who enter here. For the path of the COI is long and treacherous. Let’s shine some light on the dark mystery that is US Coast Guard regulations.

What is a COI?

Commercial ships in the USA require a license for the captain, crew, . . . but also for the ship itself. This is the certificate of inspection (COI). This little piece of paper let’s you know that the ship was built to certain safety standards. It covers major items such as:

- Fire protection

- Sprinklers

- Emergency bilge pumps

- Vessel stability

- Hull strength

And a host of other details. Everything from non-combustible drapes down to the hydraulic system for the rudder.

Not every commercial ship needs a COI. But for those that do require it, the process of a COI is long and expensive. USCG tries to limit that burden, depending on the ship type. It comes down to risk. If that ship had a disaster, what is the risk to life and the environment, with emphasis on protecting life. For example, a 6000 passenger cruise ship definitely maintains a COI (if it’s under USCG jurisdiction). But an unmanned deck barge doesn’t require a COI. If the barge sank, that endangers no lives. No one onboard the barge. And a lump of metal presents little risk to the environment, even sitting on the seabed. For anything else in-between ask a naval architect.

One common exception is the Uninspected Passenger Vessel, commonly called the 6-pack. Passenger boats that carry a maximum of 6 passengers do not need a COI. Some people tell you the limit is 12 passengers. That’s only true under very specific conditions. A customer can charter an uncrewed boat, carrying up to 12 passengers. And then separately, that customer can hire a crew to operate the boat. But chartering is very different from being a passenger. If you charter a boat, you are legally responsible for any damage that boat does, not the boat owner.

And uninspected doesn’t make the boat unregulated. The ship still needs a licensed captain. It you want to operate a 6-pack, check with the local USCG and make sure you understand the limits very clearly. Now, let’s set aside the complicated rules of the 6-pack and dive into something worse: how to get a COI.

Application Process

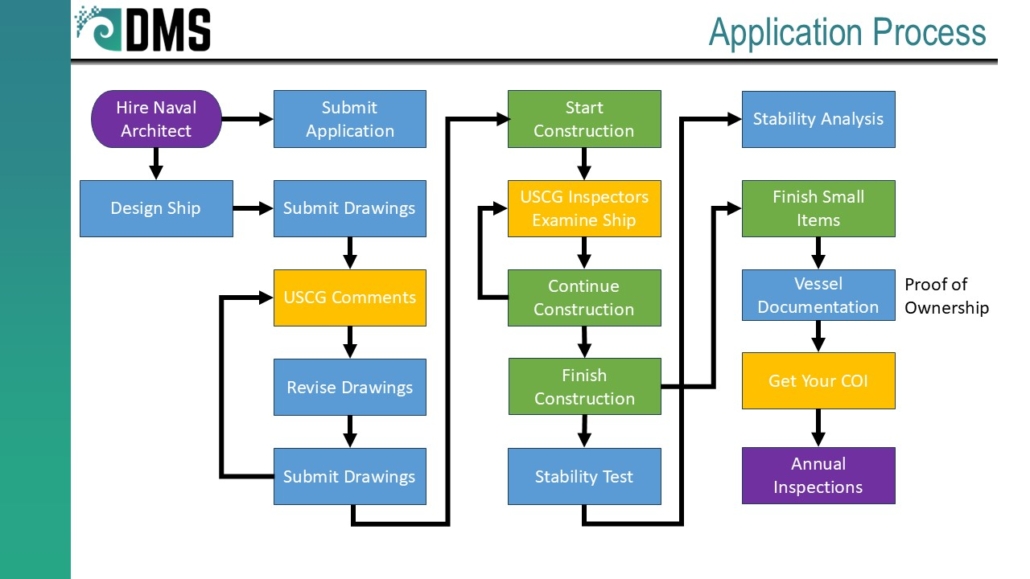

The process starts by hiring a naval architect. The naval architect acts as your agent with the USCG and organizes everything. We usually start with an informal call to the local USCG unit. Inform them of new COI that will happen soon. And request guidance on any unique vessel features.

Then the real work starts. USCG needs drawings and documentation for every part of your vessel. Every pipe system, every structural frame, the electrical system, all the doorways . . . all of it. The exact requirements change depending on the vessel. USCG requires these drawings for two reasons. First, to prove the vessel meets all the requirements. And second, if the vessel ever sinks, they need the documentation for forensic investigations to find out what went wrong.

After the naval architect prepares everything, we formally kick off the application process.

- Email in form CG-3752 to the local USCG office, requesting a COI. Nearly all communications happen through email.

- We then submit all the drawings and documentation for the vessel. Most of these documents get reviewed by the Maritime Safety Center (MSC), located in Washington D.C. That office is full of engineers who check plans and ensure everything meets the safety requirements. MSC may also ask for more drawings or further details.

- USCG typically has comments and needs small adjustments to the drawings. The naval architect makes necessary changes and resubmits. We continue this process with every drawing until USCG approves everything. On a small boat, this may involve anywhere from 15-30 drawings. On large passenger ships, expect over 100 drawings.

- As the review process finishes, we start construction of the new ship. The shipyard coordinates with the local USCG office, who sends out inspectors. The inspectors check that the ship matches the drawings approved by USCG. They also have a working knowledge of the regulations and warn you if any changes violate the rules.

- After finishing construction, we conduct a stability test. This measures the vessel’s exact weight and center of gravity. (There are several options for the exact type of test.) This landmark usually signals the last major milestone in the COI process.

- Following the test, the naval architect feeds that information into a stability analysis. We make sure the ship doesn’t flip over in rough weather. Sumit that information to MSC for final review.

- Finish up the list of minor items with USCG. Small tasks always come up.

- Get the vessel documented. Fancy word for registering the vessel with the national database. Just like you register a car with your state government, or even a small boat. But commercial ships get registered with the national USCG database, because they fall under USCG jurisdiction. With the registration, ownership of the boat officially transfers to you.

- You finally get the COI! That paper arrives in the mail and you can legally take on passengers.

Don’t forget to maintain the COI. The COI requires annual inspections of the vessel. Every year, you need to contact the local USCG office and schedule an inspection. And every five years, the boat goes into drydock to inspect the underwater portion of the hull. USCG checks all the systems still work and the vessel remains in good service. Most likely, they will find a few small items that you need to correct. (For small items, your ship remains in service while you correct them.)

Schedule

The biggest surprise for the COI process: it takes a VERY long time. Most owner’s expect something similar to filing your taxes. Fill out the paperwork and done within a month or two. Nope. A COI application takes around 12 months or more to complete. Emphasis on “or more.”

Why so long? Every time we submit a drawing or document, USCG has a month to review it. Remember that USCG normally requests revisions, small changes on everything. A typical review cycle will involve 2-3 rounds of submissions. That’s 2-3 months for every single drawing! Plus time for the inspectors to examine the physical vessel. Not to mention: sometimes USCG gets delayed, requiring 2-3 months for a single review. Unfortunately, not much I can do about it. USCG holds all the cards. The slow pace of a COI application depends primarily on USCG.

Consider the USCG review process for your business implications. When planning a schedule for the COI process: DON’T. Don’t commit to a start date for the vessel. Don’t advertise events for the ship. Don’t expect any specific schedule until we are 95% done with the COI process.

Return on Investment

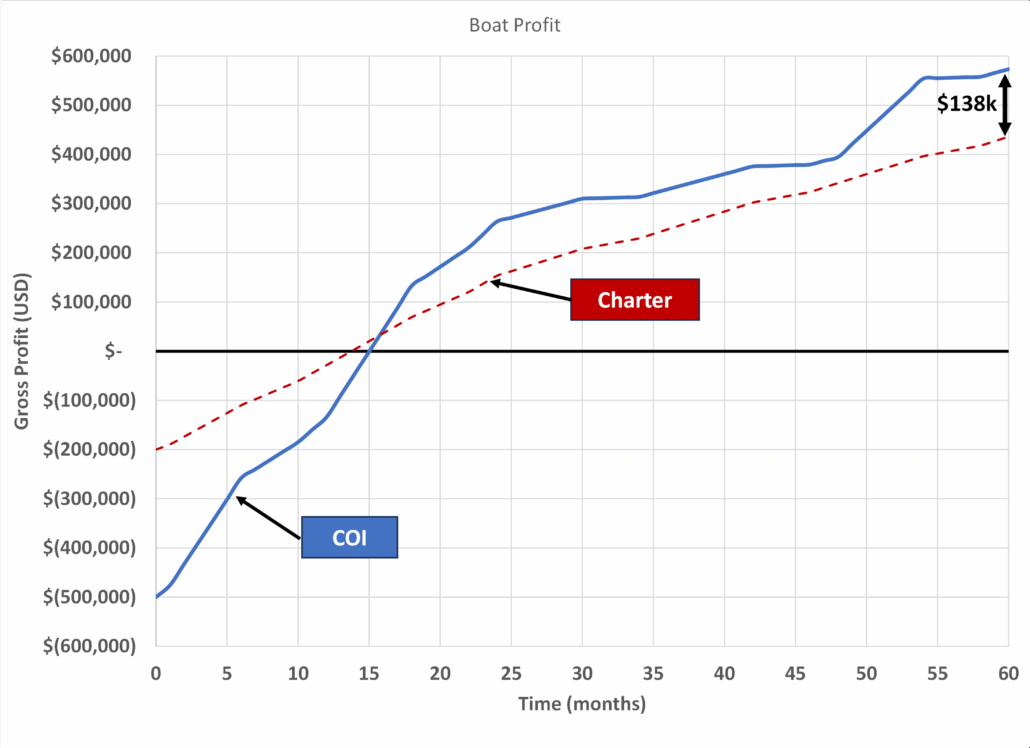

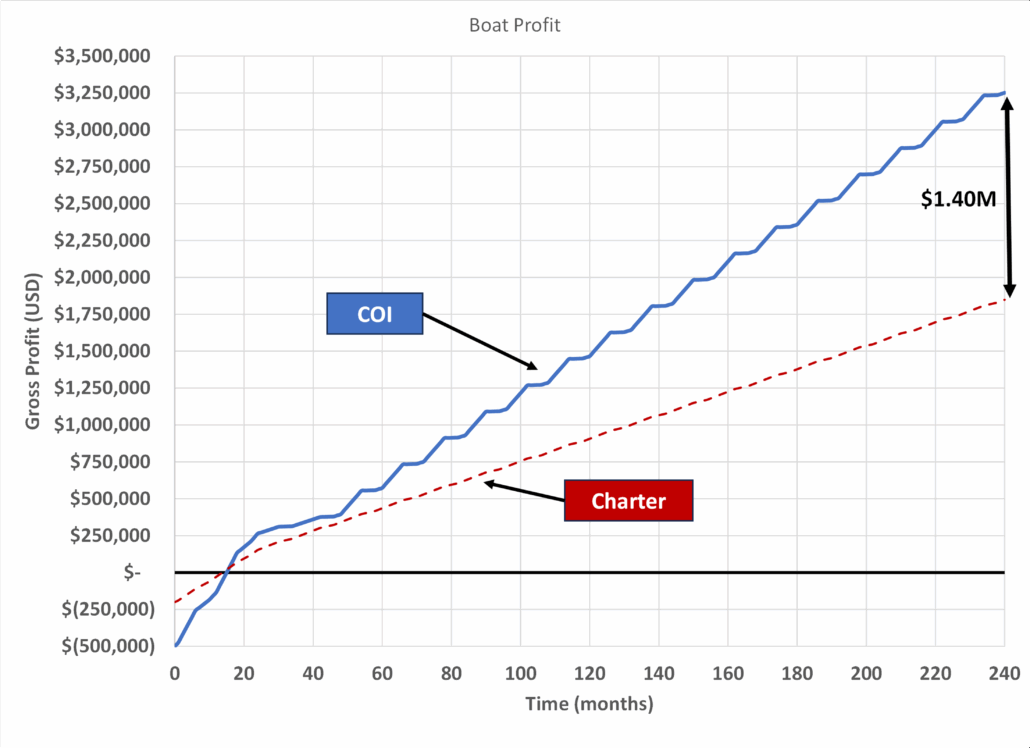

With all this effort, you probably entertain second thoughts about the COI. Is it worth it? Can you profit from such a large investment of time, money, and stress? YES! The COI offers many advantages over a smaller charter boat: more passengers; greater flexibility; a larger ship with more revenue. All this adds up to a definite profit advantage compared to charter boats.

If your business just charters out small boats, you get a cost advantage at first. Those small boats are basically just yachts or pontoon boats. They cost less than a COI vessel. But they also limit the revenue. You can only charge so much for the entire vessel, regardless of how many passengers board it.

But with a COI ship, more passengers means more revenue. We quickly discover that beyond a minimum safety threshold, adding space for more passengers becomes relatively cheap. More revenue with little extra cost. That’s how the COI gains an advantage. And over time, that advantage multiplies.

Look at Figure 5‑1, which shows typical profit projections for a small COI boat vs. a pontoon charter boat. Both boats started with a 2 year bank loan at 6.5% interest rate (although the charter boat cost less, with a smaller loan). In less than two years (24 months), both boats earned back their initial investment and generate a profit. But the COI generates a TON more profit. After 20 years (240 months), this amounts to the COI vessel earning $1.4M more in gross profit. A tidy nest egg.

Conclusion

The COI demands plenty of effort to first acquire. It’s a major investment. But once achieved, that COI becomes a huge asset. A ship full of passengers generates loads of revenue. Far more profitable than a small 6-pack boat. My best advice: recognize that the COI application is a game of endurance. Prepare financially, mentally, and emotionally. This time, money can’t buy a faster schedule. The only option is to wait out the process. But once finished, you get a very profitable ship. The wait is worth it.