One of the biggest challenges for polar operations: the remote location. You find yourself far away from ANYTHING. Beyond normal radio communication (VHF). Beyond the operating range of regular coast guard. Traveling into waters that search and rescue can’t enter. As a polar class icebreaker, you are already the biggest, baddest ship in the region.

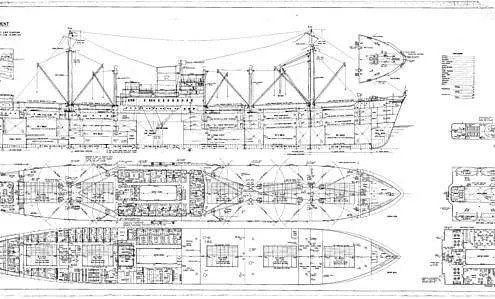

If you get in trouble, we can’t find anyone better equipped. You’re it. A polar vessel needs facilities for self-rescue. This includes extended machine shops to build any component on the ship. Storage rooms packed with spare components. Even spare propeller blades. Most polar class icebreakers include a full set of spare propeller blades, sufficient to replace an entire propeller. And a crane to move those blades and lower them over the side. Plus divers trained to replace the blades in freezing cold water. If I look long enough, I can even find a spare piston head somewhere in the storage closet. Polar icebreakers prepare to fix anything. When trouble calls, a polar icebreaker provides its own rescue.

Remote operation also includes less dependence on communication. A typical cargo ship checks their position from GPS satellites every few minutes; they receive daily updates on weather predictions for the region; and a daily check in with home base concerning resupply and coordination. All those features become less reliable in polar waters. GPS and satellite communication experience sparse reception, since fewer satellites orbit our poles. No more daily weather updates. Hence, many polar icebreakers include helicopter support. This provides the ability to fly around and scout out the best ice route. Without satellite assistance, we provide our own navigation guidance.

Traditional navigation also encounters challenges. Outside of GPS, a ship may have magnetic and gyro compasses to detect their direction. But magnetic compasses depend on the alignment of the Earth’s magnetic field. Near the North and South poles, that magnetic field isn’t always consistent. And the gyro compass uses a rotating gyroscope to align with the Earth’s rotation axis. Except, at the poles, you land on top of the axis of rotation. Makes it a lot harder to determine direction. Clearly, we found methods to compensate. It just shows that at the Polar regions, the simplest things become unexpectedly challenging.